A conference in Berlin has recalled how in 1989 an ecumenical assembly mobilised dissent in the former East Germany in the run-up to a peaceful revolution that led to the collapse of communism and the end of the Berlin Wall.

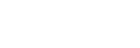

Meeting three times between February 1988 and April 1989, the Ecumenical Assembly brought together Protestant, Roman Catholic and Orthodox leaders, lay people and grass-roots activists to respond to issues of justice, peace and creation in East Germany and the wider world.

The results of the assembly were set down in 12 texts based on a “preferential option” for the poor, for nonviolence and for the protection and promotion of life.

Despite East Germany having strict communist rule, the assembly made unprecedented demands for change, including secret ballots for elections, the freedom of expression and the possibility to travel freely, and the right to form independent associations.

“The Ecumenical Assembly is part of the history of the peaceful revolution,” said Markus Meckel, one of the organizers of the Berlin conference, which gathered 300 people in the city’s Catholic Academy on 27 March.

Many delegates at the Ecumenical Assembly went on to found the independent political parties and citizens’ movements that were formed in autumn 1989 as part of the widespread protests against the communist authorities in the German Democratic Republic, the official name for East Germany.

“It was part of the movement that fundamentally changed the German Democratic Republic and then the whole of Germany,” said Berlin’s Protestant bishop, Markus Dröge.

Meckel himself was a Protestant pastor and peace activist who after the peaceful revolution was elected to the East German parliament in March 1990. He then became the German Democratic Republic’s foreign minister, helping to negotiate the unification of East and West Germany in October 1990.

Historian Katharina Kunter described the assembly as a “platform for church and political protest.”

The ecumenical gathering followed an appeal at the 1983 Vancouver assembly of the World Council of Churches (WCC) for a “Conciliar Process” for justice, peace and the integrity of creation, she noted.

Former WCC general secretary Konrad Raiser recalled how the Conciliar Process had been inspired by the witness of the German Lutheran theologian Dietrich Bonhoeffer, who was executed for his opposition to National Socialism.

Bonhoeffer had called for a binding witness by churches to peace at a time “when it was clear that the National Socialist regime was preparing for a war in Europe,” said Raiser.

“This legacy is today as urgent as it was then,” he said. “The underlying feeling that we face a real existential threat is not any less than it was.”

Annemarie Müller, part of the preparatory group for the Ecumenical Assembly in East Germany, pointed to the ecumenical dimension of the gathering.

“We felt we are not simply Protestants, not simply Catholics, but we are Christians,” she said.

Often the discussions in the working groups of the assembly got very heated, “but we were able to join together in prayer,” Müller said. “When we were no longer able to speak to each other, we gathered together and said prayers for peace.”

World Council of Churches, oikoumene.org