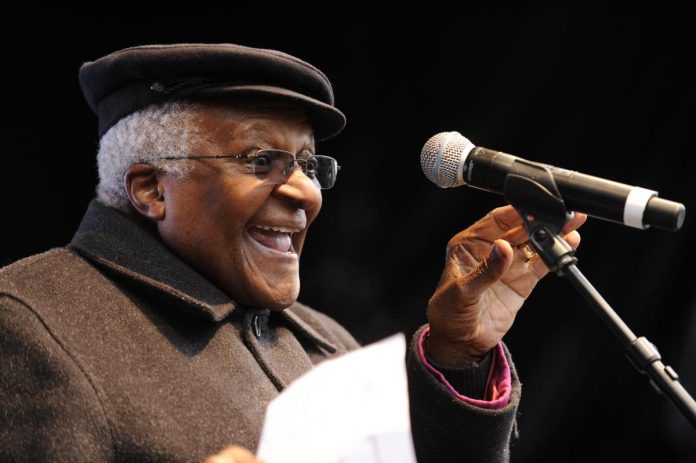

Desmond Mpilo Tutu was a unique character. His contagious sense of humour and laughter has helped to resolve many critical situations in South Africa’s political and church life. He was able to break almost any deadlock. He shared with us the laughter and grace of God many a time. He was a man of God with all the oddities that come with it. Read the tribute by Baldwin Sjollema.

Desmond Tutu: Pastor of the Nation – A Tribute

Desmond Mpilo Tutu was a unique character. His contagious sense of humour and laughter has helped to resolve many critical situations in South Africa’s political and church life. He was able to break almost any deadlock. He shared with us the laughter and grace of God many a time. He was a man of God with all the oddities that come with it.

He was humble. I remember watching his emotions when, as chairperson of South Africa’s Truth and Reconciliation Commission (TRC), during hours, weeks, months he listened intensely to the cries and sorrows of thousands of black victims of apartheid. At that moment he became the pastor of the nation. Nelson Mandela had appointed him to the daunting task in 1994. At the opening session Tutu spoke with untypical brevity: “For once”, he said, “the Archbishop does not have many words, thank goodness.”

Desmond has been instrumental in developing the notion of Ubuntu: a person is a person because of other people; it implies mutual responsibility and compassion. It became the guiding principle of the TRC and has been written into the South African Constitution.

Tutu stressed time and again the TRCs central role of forgiveness. No future without forgiveness. “You can only be human in a humane society. If you live with hatred in your heart, you dehumanize not only yourself, but your community”. But his vision – and that of Mandela- was not shared by all. Others would say that it was too big a demand to make on anybody, especially people who had suffered and were abused. More modestly, they argued that learning to live together and respect one another is all one could ask.

Back in the 1970s Desmond and I were colleagues at the WCC. He was working for the Theological Education Fund (TEF) based in London whereas I was working in the controversial Programme to Combat Racism (PCR) in Geneva which supported the liberation movement. We were not always on the same wavelength. At that time Desmond had to be careful not to be too outspoken against the Pretoria regime in order not burn his bridges at home. But his attitude changed radically after his return to South Africa when he was appointed dean of Johannesburg in 1975 and one year later Anglican bishop of Lesotho, then General Secretary of the South African Council of Churches (SACC) and finally the first black Archbishop of Cape Town (1987).

In the 1980s when the struggle against apartheid reached its peak, Desmond was fearless in predicting black rule: “We need Nelson Mandela”, he said in April 1980, “because he is almost certainly going to be that first black prime minister.” His great courage and moral authority were recognized by the international community when he was awarded the Nobel Peace Prize in 1984.

Together with many other church leaders in South Africa, Desmond was in the forefront of the struggle, providing leadership at both local and national levels. Churches became meeting places and centres of information. Desmond was not frightened to speak the truth to those that were in power: straightforward and with humour. He was irrepressible.

At the end of the 1980s President Botha imposed a nationwide state of emergency, giving the police drastically more powers. Black leadership was either in hiding or in jail. The only gatherings permitted were those in churches. At that time Tutu as the Bishop of Johannesburg preached a militant sermon in the cathedral, asking with his arms outstretched: “Why are we allowing this country to be destroyed?”

When liberation finally came and a democratically elected parliament started its work, he exclaimed “I love this dream. You sit in the balcony and look down and count all the terrorists. They are all sitting there passing laws. It is incredible!” Unabated he continued speaking out against injustice, corruption and the abuse of power. When MPs came under fire accepting big salaries, Tutu commented: “The Government stopped the gravy train long enough to get on it.” This and many other pronouncements earned him much criticism from the new government.

I shall remember Desmond Tutu foremost as a friend and colleague who reminded us time and again that instead of racism, disunity, enmity and alienation, “God has intended us for fellowship, for koinonia, for togetherness, without destroying our distinctiveness, our cultural identity”.